-

play_arrow

play_arrow

Fresh 106 Fresh 106

-

play_arrow

play_arrow

London Calling Podcast Yana Bolder

A Family Torn Apart by the State

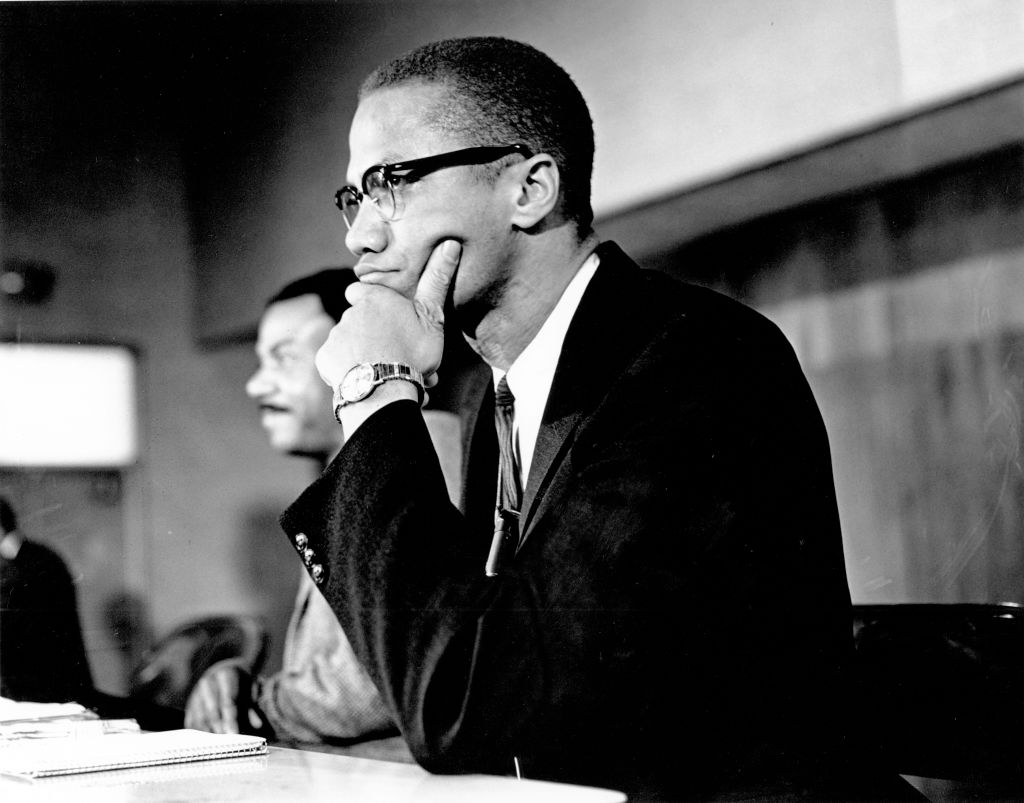

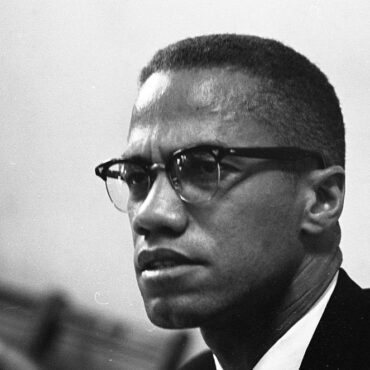

As we celebrate the centennial birthday of El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz—known to the world as Malcolm X—let us resist the urge to sanitize his legacy.

We shouldn’t spend this moment only posting his image or quoting his speeches stripped of their revolutionary meaning. We must also remember him as the boy this country tried to annihilate—long before he became the man Ossie Davis eulogized as “our living, Black manhood… our own Black shining prince—who didn’t hesitate to die, because he loved us so.”

Malcolm X was born Malcolm Little on May 19, 1925, in Omaha, Nebraska, into a household steeped in Black nationalist politics and resistance.

Malcolm’s father, Earl Little, was a Baptist preacher and an outspoken organizer with Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). His sermons lifted up Black pride, economic independence, and Pan-Africanist solidarity. His mother, Louise Norton Little, was equally formidable: a Grenadian-born writer who contributed to Garvey’s Negro World newspaper and kept the Garvey movement’s flame alive in their family home. Together, they taught their children that Black people could—and must—liberate themselves.

For these beliefs, the Littles were marked, surveilled, and terrorized.

Before Malcolm could even speak, white supremacists were at his family’s doorstep. The Ku Klux Klan threatened the Little family home in Omaha, forcing them to flee to Lansing, Michigan. There, their home was firebombed by white vigilantes. And in 1931, Earl Little was found dead on the street, nearly severed by a streetcar. Though officials ruled his death an accident, the family believed he had been murdered by the Black Legion, a local terrorist white supremacist group. With that ruling, the insurance company denied Louise the life insurance that might have kept the family afloat.

The trauma of this brand of racial violence was only the beginning. What followed would be no less devastating: a slow dismantling of the Little family through a state apparatus masquerading as “child welfare.”

Surveillance Disguised as Support

After Earl Little’s death, Louise Little struggled to support her eight children. She turned to public assistance, but help came only with strings, surveillance, and contempt. Welfare caseworkers, all white, visited constantly, undermining her authority, probing her parenting, and prying into the family’s home. Malcolm later recalled that they “acted as if they owned us… as if we were their private property.” Rather than offer support, the child welfare system became a hostile presence in their lives.

Louise, proud and politically conscious, resisted their intrusions. She “talked back,” defended her children, and demanded dignity. For this, the state labeled her unstable. The relentless surveillance wore her down. In 1939, the state committed Louise to the Kalamazoo Mental Hospital. She would remain there for 26 years. Soon after, Malcolm and his siblings were stolen from their family and community and scattered into foster homes, institutions, and detention centers.

“They were as vicious as vultures,” Malcolm later wrote of the state welfare workers. “They had no feelings, understanding, compassion, or respect for my mother.” He did not mince words: “A judge had authority over me and all my brothers and sisters… nothing but legal, modern slavery, however kindly intentioned.”

What was framed as child protection was, in fact, racialized family policing—a brutal, bureaucratic dismantling of a proud Black family committed to liberation.

From the Littles to Today: A System That Still Separates

What happened to Malcolm X’s family wasn’t an isolated tragedy of the 1930s. It was—and remains—standard operating procedure for a system built on controlling Black families, not caring for them.

Today, Black families are still disproportionately targeted by the family policing system. According to a landmark study from the American Journal of Public Health, over 50% of Black children in the U.S. will experience a child welfare investigation before age 18, nearly double the rate for white children. Black children are also more likely to be removed from their homes, with nearly 10% being placed in foster care at some point during childhood. Though Black children make up only about 14% of the U.S. child population, they represent 22% of all children in foster care.

This overrepresentation isn’t due to higher rates of abuse. In fact, the vast majority of child removals stem from vague accusations of “neglect”—a category that overwhelmingly reflects poverty, not harm. In 2019, 75% of confirmed child maltreatment cases were neglect-related. Parents who lack stable housing, childcare, or access to food are labeled unfit, and their children are taken. The state punishes poverty but calls it protecting children.

Ableism and the Criminalization of Care

The family policing system is not only racist—it is profoundly ableist.

Louise Little was institutionalized, not because she posed a danger, but because she was a Black woman in mourning, under immense pressure, and because she refused to be silent about it. Instead of receiving mental health care or support, she was disappeared into a psychiatric facility. Her children were removed under the guise of her “unfitness,” and the system never looked back.

Today, this ableist logic remains intact. Parents with disabilities—especially Black parents—are far more likely to have their children removed. A national survey found that parents diagnosed with serious mental illnesses are eight times more likely to face CPS involvement, and 26 times more likely to have their children taken from them. Disabled Black mothers live with the compounded fear that asking for help will result in punishment, not support.

It is a vicious cycle: state neglect begets trauma, and trauma becomes the justification for more state violence.

Abolition Is the Only Way Forward

Malcolm X’s early life—shaped by racist terrorism and family separation—planted the seeds of his radicalism. He saw through the lie of state benevolence. He called it what it was: legal slavery, white domination, institutionalized cruelty masked as care.

If Malcolm’s story teaches us anything, it is that our families need solidarity, not surveillance. Louise Little didn’t need to be stripped of her children; she needed respite, mental health support, and community. What the Littles needed was care, not cages. Had neighbors, kin, or even public resources been offered without strings, Malcolm might have grown up more whole. Instead, he grew up in fragments—and forged those fragments into a fire the world could not ignore.

Today, abolitionists build on that fire. We demand a world where no parent is punished for being poor or disabled. A world where no child is disappeared into the system for loving their mother too fiercely. Abolition isn’t about the absence of safety; it’s about building real safety rooted in care, not coercion.

As Malcolm once said, “Our home didn’t have to be destroyed.” And as we honor his 100th birthday, we say: no more destroyed homes, no more destroyed families, and no more destroyed communities.

Josie Pickens is an educator, writer, cultural critic, and abolitionist strategist and organizer. She is the director of upEND Movement, a national movement dedicated to abolishing the family policing system.

SEE ALSO:

Malcolm X’s Plans Before He Was Killed

Malcolm X’s Estate Sues FBI, CIA Over Assassination

, On what would have been the 100th birthday of El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz, better known as Malcolm X, writer Josie Pickens discusses the role family policing played in his childhood trauma.,  , Read More, Civil Rights & Social Justice, News Archives – Black America Web, [#item_full_content].

, Read More, Civil Rights & Social Justice, News Archives – Black America Web, [#item_full_content].

Written by: radiofresh106

Similar posts

Featured post

Latest posts

Current show

True R&B

For every Show page the timetable is auomatically generated from the schedule, and you can set automatic carousels of Podcasts, Articles and Charts by simply choosing a category. Curabitur id lacus felis. Sed justo mauris, auctor eget tellus nec, pellentesque varius mauris. Sed eu congue nulla, et tincidunt justo. Aliquam semper faucibus odio id varius. Suspendisse varius laoreet sodales.

closeUpcoming shows

Chart

Copyright 2024 Fresh 106 All Rights Reserved

Invalid license, for more info click here

Invalid license, for more info click here

Post comments (0)